Re-defining the meaning of paternalism, the American Lung Association on Tuesday boldly and unashamedly told smokers that if they quit smoking the wrong way, it doesn't count, essentially condemning the nearly 7 million Americans who are vaping instead of smoking.

In a Reuters article, the American Lung Association told the nation's smokers that: "We think there are certainly more and better ways to quit. When you're going to e-cigarettes, you're not quitting, you're switching."

The Rest of the Story

This is perverse paternalism. It is an attempt to so strongly control the lives of smokers that the American Lung Association is literally lying to smokers in trying to control their behavior.

What the American Lung Association is telling smokers is not merely that they should quit, but that they must quit in the way that the ALA tells them to or they might as well continue smoking. Thus, this message insinuates that the ALA would rather these smokers die than quit the wrong way.

Let me set the record straight and try to undo some of the damage that the American Lung Association is causing. There is no right or wrong way to quit smoking. What matters for your health is that you quit. The body doesn't know how you quit; what it knows is that you are no longer inhaling tobacco smoke with its tens of thousands of chemicals and more than 60 known human carcinogens. Whether you quit using a nicotine patch, a pill, hypnosis, vaping, acupuncture, or natural magick, you have successfully quit smoking, are no longer inhaling toxic tobacco smoke, have essentially saved your life, and I congratulate you for having accomplished the single most important - and most difficult - thing you can do to protect your health.

In contrast, the American Lung Association only congratulates you if you quit in the ways that it approves. If you quit by switching to vaping, you are not going to be congratulated by the ALA. In fact, they don't even consider you to be an ex-smoker, apparently. The ALA would redefine the clearly established definition of "former smoker" that has been used by the CDC for decades in order to avoid having to call a single-use vaper an ex-smoker.

This, of course, is lying to the American public. It simply is not true that if you switch from smoking to vaping, that you are still a smoker. You are a successful quitter, not merely a "switcher."

The public health damage being done by the American Lung Association and other anti-vaping groups with similar messages is immense. In the past year, the proportion of U.S. adults who incorrectly believe that smoking is no more hazardous than vaping rose from 38% to 47%. Thanks to the messages being disseminated by the American Lung Association and similar groups, nearly half of all adults fail to recognize that smoking is any more dangerous than vaping. This is outrageous and sinful. The health groups are doing as much to undermine the public's appreciation of the severe hazards of smoking as the tobacco companies used to do (and which led to Big Tobacco companies being recognized as adjudicated racketeers).

The natural question that arises is why is the American Lung Association going to this extreme of lying to the public in order to support a position which is clearly in direct conflict with its own avowed mission?

The answer, I have concluded, is that like so many organizations these days, the American Lung Association has lost sight of its true public health mission and is being diverted by ulterior motives, such as preserving an underlying ideology that justifies its schema with which it views the world, appeals to potential donors, and protects the organization from what it perceives as threats to its world view.

Put simply, I believe that groups like the American Lung Association are threatened by the idea that someone could possibly derive any pleasure from nicotine and that a form of nicotine use could be associated with an actual improvement in their health. This concept is simply too foreign to their world view, which cannot accommodate this notion. So rather than altering its world view, the organization has to change the facts, misrepresent the science, and re-define basic definitions in order to force what this phenomenon to fit into its world view.

Ironically, it is precisely the fact that vaping is so much safer than smoking that I think truly threatens these groups. They are comfortable with the status quo and their long-time perspective: people who smoke cigarettes and become addicted are punished because smoking is so toxic that they develop disease or die. Addiction is a human flaw and it is punished appropriately. The idea that someone could be a "nicotine addict" but be worthy of praise is just not coherent with the world view of groups like the American Lung Association. Without the natural consequences of these "addicts" dying of cancer or lung disease, the ALA must concoct its own punishment and castigation for these people.

The rest of the story, however, is that these people number in the millions. And they are people who should be congratulated for having finally succeeded in quitting smoking - something that they were unable or unwilling to do using the methods that the American Lung Association recommends.

Furthermore, the public health miracle of 2016 - an unprecedented drop in adult smoking rates (the largest year-to-year drop ever observed) - would likely not have occurred if smokers actually followed the American Lung Association's advice. Instead of having probably about 5 million adults crossed out from the current smoker category and placed into the former smokers who are vaping, we would most likely have had several million adults remain in the current smoker column.

But apparently, the American Lung Association would rather see these millions of people smoking rather than vaping because the idea that literally millions of people might be benefiting from the use of a product that contains nicotine is simply too hard to bear. It doesn't fit nicely into the organization's world view, so it must be dismantled.

...Providing the whole story behind tobacco and alcohol news.

Thursday, May 26, 2016

Tuesday, May 24, 2016

Why Anecdotal Evidence Proves that Electronic Cigarettes ARE Helpful for Smoking Cessation

One of the widest scientific misconceptions about evaluating the effectiveness of electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation - and one promulgated by anti-vaping groups and health agencies like the CDC and FDA - is that anecdotal evidence is insufficient to demonstrate that electronic cigarettes can be effective in helping smokers to quit smoking. In fact, this is a widespread fallacy. The truth is that the abundant anecdotal evidence of e-cigarettes helping many smokers quit is actually sufficient evidence to conclude that e-cigarettes are helping many smokers quit.

How can this be the case? Haven't we all been taught that anecdotal evidence is not sufficient? Aren't more rigorous research designs necessary to draw a conclusion that e-cigarettes can help some smokers quit? Since anecdotal evidence that a drug helps improve a medical condition among some patients cannot be used to conclude that the drug is an effective treatment, how can anecdotal evidence that many smokers have quit using e-cigarettes be used to conclude that e-cigarettes are effective for smoking cessation for many smokers?

The Rest of the Story

To understand this, we need to consider exactly why it is that anecdotal evidence is not sufficient to conclude that a drug is effective. Suppose a person with high blood pressure takes a medication for a week and her diastolic blood pressure is lower by 5 after one week (say it drops from 130/95 to 130/90). There are basically three possibilities that could explain the drop in blood pressure:

1. It would have dropped anyway, for reasons not related to her taking the drug.

2. The drop was caused by a placebo effect. It would have dropped had she taken a pill that just had sugar in it and not the medication.

3. The drop was caused by the medication.

So to conclude that the explanation for the drop in blood pressure is #3 above, we need to eliminate #1 and #2 as alternative explanations.

How do we eliminate #1? The way we eliminate #1 is to employ a control group: that is, a group of people with high blood pressure who are followed for one week without taking the medication to see whether their blood pressure drops anyway.

How do we eliminate #2? The way we eliminate #2 is to give a control group a placebo instead of the actual medication. If this group also experiences a decline in blood pressure, then it may be a placebo effect rather than a true drug effect.

In practice, conducting a placebo-controlled trial will address both #1 and #2 in one study because if either explanation #1 or #2 is true, then the blood pressure will drop in the control group and there will be no significant difference in blood pressure at follow-up between the treatment and the control group.

Now let's consider a behavioral outcome instead of a clinical (disease) outcome. Suppose a smoker uses a nicotine patch and at six month follow-up has stopped smoking. There are again three possible explanations:

1. The smoker would have quit anyway because by virtue of taking the nicotine patch, it is clear that he was motivated to quit and trying to quit. So it is quite plausible that the smoker would have quit even without the nicotine patch. The act of trying the patch indicated a desire to quit and a certain level of motivation to do so, above and beyond the motivation of other smokers.

2. The nicotine patch had a placebo effect. Simply by putting a patch on, it helped the person to quit due to placebo effect, not due to the actual nicotine.

3. The nicotine patch was effective in helping the smoker to quit.

To eliminate possible explanations 1 and 2, we again conduct a placebo-controlled trial, comparing the quit rate among a treatment group with the quit rate among a control group that receives a placebo patch. If either explanation 1 or 2 is correct, then there will be no difference in the cessation rate between the treatment and control groups.

Now, let's apply to same reasoning to a smoker who decides to try electronic cigarettes and is able to quit smoking. There are again three possible explanations:

1. The person may have quit smoking anyway, even had she not tried e-cigarettes. The act of trying e-cigarettes for smoking cessation could indicate a heightened level of motivation to quit smoking.

But there's a major problem with this explanation. It's not consistent with the available scientific data. The available data demonstrate that as a group, smokers who try electronic cigarettes are less motivated to quit and have much less confidence in their ability to quit. In fact, the very reason that smokers turn to e-cigarettes in the first place is that they have been unable to quit using other methods and have no self-efficacy regarding their ability to quit smoking otherwise. The data also show that smokers who try e-cigarettes tend to have higher levels of nicotine dependence and are thus much less likely to quit. In other words, the evidence supports the contention that the alternative to not trying e-cigarettes for most vapers is not quitting, but continuing to smoke. This alternative explanation therefore does not appear to hold water in most cases.

2. The person may have quit smoking due to a placebo effect. The act of using the e-cigarette (which simulates smoking) may be the reason for the successful cessation.

But there's a major problem with this explanation as well. The placebo effect is precisely the "mechanism of action" of vaping. It is a huge part of the reason why vaping could potentially be effective for cessation. The whole point of vaping products is to substitute for smoking by simulating the smoking experience. So in arguing that the observed association between vaping and smoking cessation is a placebo effect, one is actually arguing that the smoking cessation was a consequence of the e-cigarette use, since it works through a placebo effect. Therefore, this alternative explanation does not refute the third explanation: that the smoking cessation was attributable to the use of the e-cigarette.

The rest of the story is that the abundant anecdotal evidence of smokers quitting successfully using e-cigarettes is strong evidence that e-cigarettes are - for these smokers - effective in helping them quit. The FDA's view on this issue is misguided because it doesn't understand the basic scientific reasoning behind this relationship. The agency is used to evaluating drug studies, which must include placebo-controlled trials rather than rely on anecdotal evidence.

Please note: I am not arguing that clinical trials of smoking cessation with e-cigarettes compared to other approaches are not needed. I've made it very clear that conducting such trials should be a research priority. Neither am I arguing that anecdotal evidence that e-cigarettes can help smokers quit provides any estimate of the magnitude of the effect: we cannot, from the anecdotal evidence, determine what proportion of smokers who attempt to quit using e-cigarettes will succeed.

However, the argument that we do not have evidence to conclude that e-cigarettes can help smokers to quit is fallacious. The abundant anecdotal evidence available provides substantial evidence that e-cigarettes can and do help many smokers to quit.

How can this be the case? Haven't we all been taught that anecdotal evidence is not sufficient? Aren't more rigorous research designs necessary to draw a conclusion that e-cigarettes can help some smokers quit? Since anecdotal evidence that a drug helps improve a medical condition among some patients cannot be used to conclude that the drug is an effective treatment, how can anecdotal evidence that many smokers have quit using e-cigarettes be used to conclude that e-cigarettes are effective for smoking cessation for many smokers?

The Rest of the Story

To understand this, we need to consider exactly why it is that anecdotal evidence is not sufficient to conclude that a drug is effective. Suppose a person with high blood pressure takes a medication for a week and her diastolic blood pressure is lower by 5 after one week (say it drops from 130/95 to 130/90). There are basically three possibilities that could explain the drop in blood pressure:

1. It would have dropped anyway, for reasons not related to her taking the drug.

2. The drop was caused by a placebo effect. It would have dropped had she taken a pill that just had sugar in it and not the medication.

3. The drop was caused by the medication.

So to conclude that the explanation for the drop in blood pressure is #3 above, we need to eliminate #1 and #2 as alternative explanations.

How do we eliminate #1? The way we eliminate #1 is to employ a control group: that is, a group of people with high blood pressure who are followed for one week without taking the medication to see whether their blood pressure drops anyway.

How do we eliminate #2? The way we eliminate #2 is to give a control group a placebo instead of the actual medication. If this group also experiences a decline in blood pressure, then it may be a placebo effect rather than a true drug effect.

In practice, conducting a placebo-controlled trial will address both #1 and #2 in one study because if either explanation #1 or #2 is true, then the blood pressure will drop in the control group and there will be no significant difference in blood pressure at follow-up between the treatment and the control group.

Now let's consider a behavioral outcome instead of a clinical (disease) outcome. Suppose a smoker uses a nicotine patch and at six month follow-up has stopped smoking. There are again three possible explanations:

1. The smoker would have quit anyway because by virtue of taking the nicotine patch, it is clear that he was motivated to quit and trying to quit. So it is quite plausible that the smoker would have quit even without the nicotine patch. The act of trying the patch indicated a desire to quit and a certain level of motivation to do so, above and beyond the motivation of other smokers.

2. The nicotine patch had a placebo effect. Simply by putting a patch on, it helped the person to quit due to placebo effect, not due to the actual nicotine.

3. The nicotine patch was effective in helping the smoker to quit.

To eliminate possible explanations 1 and 2, we again conduct a placebo-controlled trial, comparing the quit rate among a treatment group with the quit rate among a control group that receives a placebo patch. If either explanation 1 or 2 is correct, then there will be no difference in the cessation rate between the treatment and control groups.

Now, let's apply to same reasoning to a smoker who decides to try electronic cigarettes and is able to quit smoking. There are again three possible explanations:

1. The person may have quit smoking anyway, even had she not tried e-cigarettes. The act of trying e-cigarettes for smoking cessation could indicate a heightened level of motivation to quit smoking.

But there's a major problem with this explanation. It's not consistent with the available scientific data. The available data demonstrate that as a group, smokers who try electronic cigarettes are less motivated to quit and have much less confidence in their ability to quit. In fact, the very reason that smokers turn to e-cigarettes in the first place is that they have been unable to quit using other methods and have no self-efficacy regarding their ability to quit smoking otherwise. The data also show that smokers who try e-cigarettes tend to have higher levels of nicotine dependence and are thus much less likely to quit. In other words, the evidence supports the contention that the alternative to not trying e-cigarettes for most vapers is not quitting, but continuing to smoke. This alternative explanation therefore does not appear to hold water in most cases.

2. The person may have quit smoking due to a placebo effect. The act of using the e-cigarette (which simulates smoking) may be the reason for the successful cessation.

But there's a major problem with this explanation as well. The placebo effect is precisely the "mechanism of action" of vaping. It is a huge part of the reason why vaping could potentially be effective for cessation. The whole point of vaping products is to substitute for smoking by simulating the smoking experience. So in arguing that the observed association between vaping and smoking cessation is a placebo effect, one is actually arguing that the smoking cessation was a consequence of the e-cigarette use, since it works through a placebo effect. Therefore, this alternative explanation does not refute the third explanation: that the smoking cessation was attributable to the use of the e-cigarette.

The rest of the story is that the abundant anecdotal evidence of smokers quitting successfully using e-cigarettes is strong evidence that e-cigarettes are - for these smokers - effective in helping them quit. The FDA's view on this issue is misguided because it doesn't understand the basic scientific reasoning behind this relationship. The agency is used to evaluating drug studies, which must include placebo-controlled trials rather than rely on anecdotal evidence.

Please note: I am not arguing that clinical trials of smoking cessation with e-cigarettes compared to other approaches are not needed. I've made it very clear that conducting such trials should be a research priority. Neither am I arguing that anecdotal evidence that e-cigarettes can help smokers quit provides any estimate of the magnitude of the effect: we cannot, from the anecdotal evidence, determine what proportion of smokers who attempt to quit using e-cigarettes will succeed.

However, the argument that we do not have evidence to conclude that e-cigarettes can help smokers to quit is fallacious. The abundant anecdotal evidence available provides substantial evidence that e-cigarettes can and do help many smokers to quit.

Thursday, May 19, 2016

Why is the American Cancer Society Lying to Its Members About the E-Cigarette Regulations?

In an urgent action alert, the American Cancer Society (through its Cancer Action Network) is encouraging its members to write their federal legislators and demand that Congress not strip the FDA of its authority to regulate electronic cigarettes.

The "suggested" letter which the ACS pre-populates for its members states: "Congress should not strip FDA of its oversight authority when electronic cigarette use by high school students has jumped to 16 percent in a very short time... ."

This action alert seems to be clearly informing ACS members that Congress is considering stripping the FDA of its authority to oversee the regulation of electronic cigarettes.

The Rest of the Story

Now why is it necessary for the American Cancer Society to lie about the pending Congressional legislation, which absolutely does not strip the FDA of its authority to regulate electronic cigarettes. The legislation would merely change the predicate date for new products, meaning that it would allow vaping products now on the market to continue to compete against cigarettes for a share of the nicotine market, but in a much safer, tobacco-free form. The FDA would still have the authority to regulate vaping products and in fact, the Cole-Bishop amendment would force the agency to be more aggressive in its regulations by requiring it to set uniform safety standards for vaping products.

I don't see the inherent value in the American Cancer Society lying to its members. Does it think its membership is too stupid to be able to handle a more subtle and nuanced message? Does it even care about the truth, or is it just using its members as pawns on a chessboard to manipulate them to do its work for it? Does the ACS not see the damage it could be causing to itself, its reputation, and its relationship with its membership if members find out that they were being lied to? What is wrong with being candid, frank, and transparent? I know that we don't expect that from our politicians, but we should it expect it from the non-profit public health advocacy groups.

I had to change the pre-populated text of my message in order to exculpate the lie and replace it with the truth. I told my Congressmembers that in contrast to what the ACS told me to tell them, the Cole-Bishop amendment would not strip the FDA of its regulatory authority over e-cigarettes, but instead would strengthen it by forcing the agency to promulgate uniform safety standards as well as to regulate e-cigarette marketing, something it failed to do in its deeming regulations. The Cole-Bishop amendment would not strip the FDA of its regulatory authority. Quite the opposite. It would strengthen the FDA's regulatory authority by forcing it to actually do something to protect the health of the American people, rather than to simply create a gigantic bureaucracy that accomplishes little else than to shield toxic tobacco cigarettes from competition from a much safer, tobacco-free alternative.

The "suggested" letter which the ACS pre-populates for its members states: "Congress should not strip FDA of its oversight authority when electronic cigarette use by high school students has jumped to 16 percent in a very short time... ."

This action alert seems to be clearly informing ACS members that Congress is considering stripping the FDA of its authority to oversee the regulation of electronic cigarettes.

The Rest of the Story

Now why is it necessary for the American Cancer Society to lie about the pending Congressional legislation, which absolutely does not strip the FDA of its authority to regulate electronic cigarettes. The legislation would merely change the predicate date for new products, meaning that it would allow vaping products now on the market to continue to compete against cigarettes for a share of the nicotine market, but in a much safer, tobacco-free form. The FDA would still have the authority to regulate vaping products and in fact, the Cole-Bishop amendment would force the agency to be more aggressive in its regulations by requiring it to set uniform safety standards for vaping products.

I don't see the inherent value in the American Cancer Society lying to its members. Does it think its membership is too stupid to be able to handle a more subtle and nuanced message? Does it even care about the truth, or is it just using its members as pawns on a chessboard to manipulate them to do its work for it? Does the ACS not see the damage it could be causing to itself, its reputation, and its relationship with its membership if members find out that they were being lied to? What is wrong with being candid, frank, and transparent? I know that we don't expect that from our politicians, but we should it expect it from the non-profit public health advocacy groups.

I had to change the pre-populated text of my message in order to exculpate the lie and replace it with the truth. I told my Congressmembers that in contrast to what the ACS told me to tell them, the Cole-Bishop amendment would not strip the FDA of its regulatory authority over e-cigarettes, but instead would strengthen it by forcing the agency to promulgate uniform safety standards as well as to regulate e-cigarette marketing, something it failed to do in its deeming regulations. The Cole-Bishop amendment would not strip the FDA of its regulatory authority. Quite the opposite. It would strengthen the FDA's regulatory authority by forcing it to actually do something to protect the health of the American people, rather than to simply create a gigantic bureaucracy that accomplishes little else than to shield toxic tobacco cigarettes from competition from a much safer, tobacco-free alternative.

Tuesday, May 17, 2016

American Lung Association Disseminates Negligent Medical Advice About Vaping

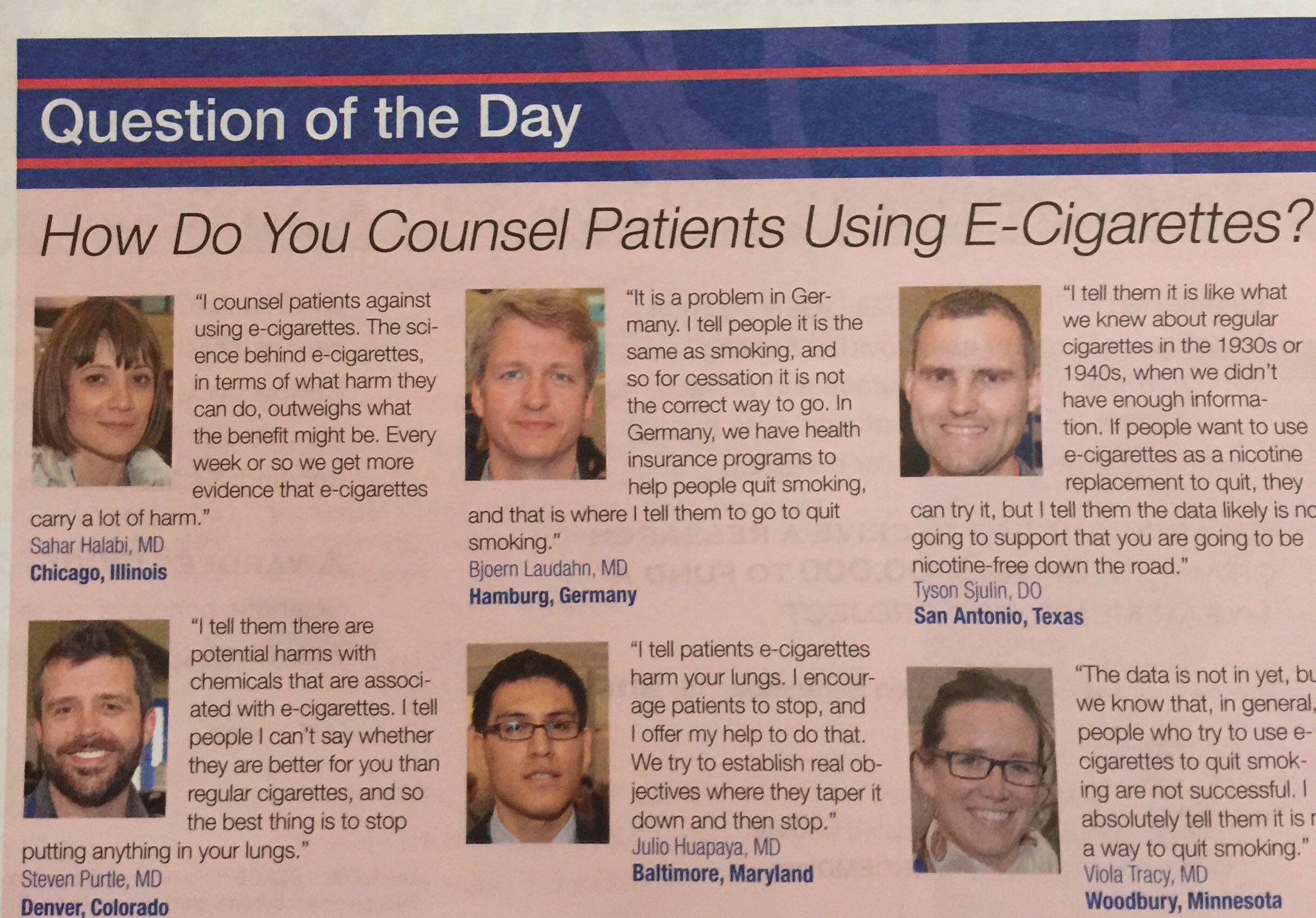

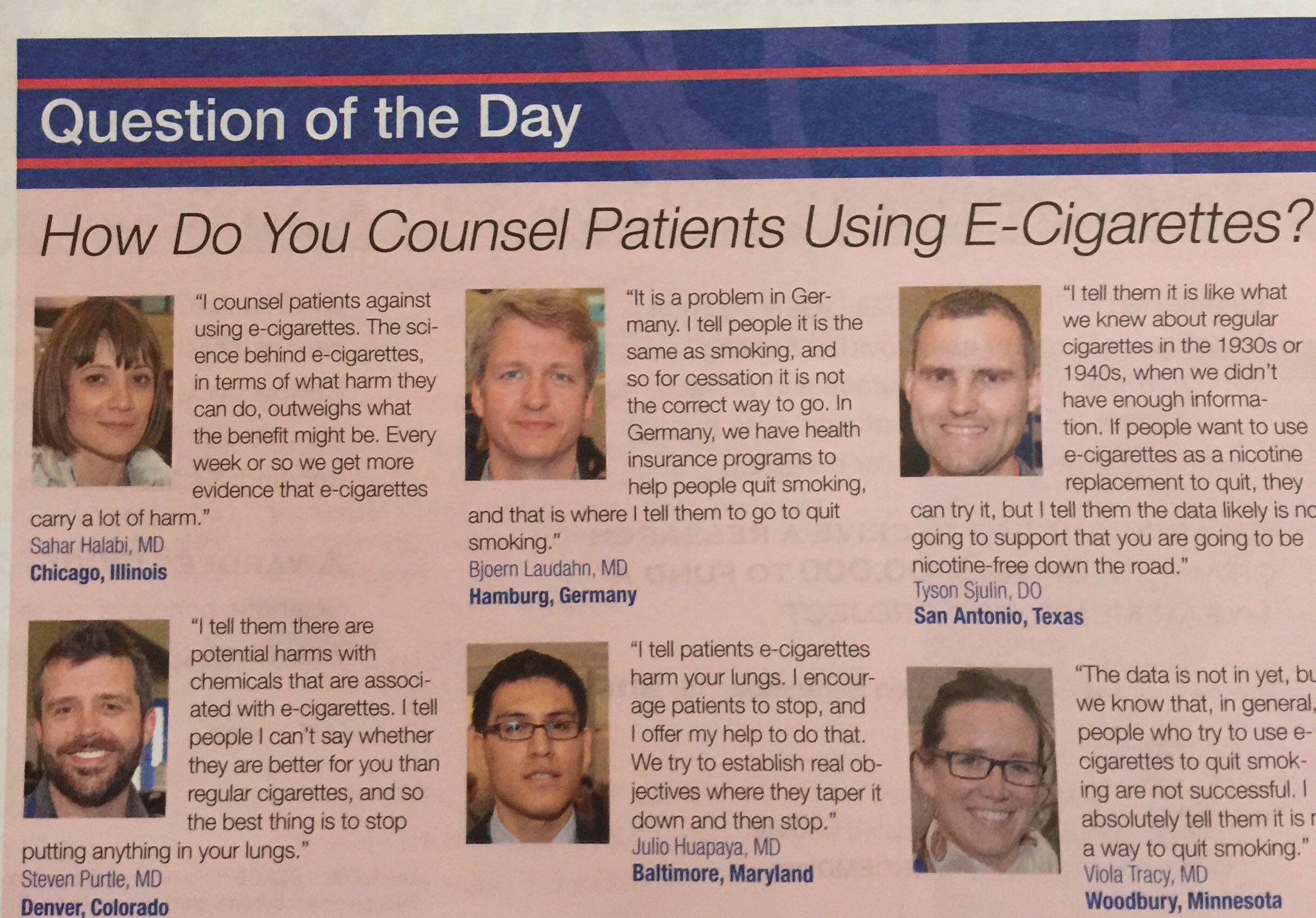

The president of the American Lung Association yesterday disseminated negligent medical advice regarding vaping through a tweet that included advice from six physicians.

Each of these six physicians provides negligent medical advice regarding smoking cessation using electronic cigarettes.

1. Chicago: This advice is negligent because it misrepresents the benefit-risk profile of electronic cigarette use for the individual patient. The physician is telling all smokers that the risks of trying e-cigarettes outweighs the potential benefits. But this is not at all consistent with the science. The science unequivocally demonstrates that there are tremendous medical benefits to patients who are able to quit or cut down substantially using e-cigarettes. And there are essentially no harms because smokers who use e-cigarettes are precisely those who believe they are unable to quit using other methods. This is a complete distortion of the risk-benefit ratio for the individual patient, and it therefore constitutes negligent medical advice.

2. Germany: This advice is negligent because the physician is telling patients that vaping is the same as smoking. This is categorically false. Vaping involves no tobacco whatsoever, and it involves no combustion. E-cigarette aerosol eliminates tens of thousands of the chemicals present in tobacco smoke, including more than 60 known human carcinogens. Switching from smoking to vaping results in dramatic and immediate improvement in respiratory symptoms and lung function. This physician is spreading false information, and it therefore constitutes negligent medical advice.

3. Texas: Like the physician from Germany, this physician is telling patients that e-cigarette health risks are analogous to those for real cigarettes. This is false information, and the medical advice is therefore negligent.

4. Colorado: This physician is telling patients that e-cigarettes are likely no safer than tobacco cigarettes. This is categorically false. Vaping involves no tobacco whatsoever, and it involves no combustion. E-cigarette aerosol eliminates tens of thousands of the chemicals present in tobacco smoke, including more than 60 known human carcinogens. Switching from smoking to vaping results in dramatic and immediate improvement in respiratory symptoms and lung function. This physician is spreading false information, and it therefore constitutes negligent medical advice.

5. Baltimore: This physician is telling patients that vaping harms their lungs. However, there is no clinically meaningful evidence to back this up. While e-cigarette aerosol is a mild respiratory irritant, it has not been shown to affect lung function as measured by spirometry. And it certainly is going to do a lot less harm than continuing to smoke. This stops just short of being negligent medical advice.

6. Minnesota: This physician is telling patients that using e-cigarettes is not a way to quit smoking. Well, it certainly has been a way to quit smoking for hundreds of thousands of Americans who quit smoking by switching to vaping. It is irresponsible for this physician to essentially lie to her patients about the fact that e-cigarettes have helped so many tens of thousands of people to quit smoking. It may not be the way that she wants them to quit, but it is a legitimate way to quit. For putting her own concerns over the best interests of the patient, this is negligent medical advice.

The Rest of the Story

It is difficult to understand what the American Lung Association's objective is here. The effect of this communication is certainly going to be to discourage quit attempts among thousands of smokers who might otherwise have been able to achieve smoking cessation using e-cigarettes. And it might also dissuade thousands of ex-smokers from continuing to vape and instead, cause them to return to smoking. Either way, I don't see how this is in any way helping to improve lung health in this country.

It is, however, public health malpractice, which I define as advice which when given to an individual patient would constitute medical malpractice, but which is instead being disseminated to the general public.

For example, if I tell my patient that vaping is just as hazardous as smoking and therefore I advise my patient not to quit using e-cigarettes, I would consider that negligent medical advice because it is false information and it had the effect of causing the patient to assume an increased risk that he otherwise might not have assumed. Thus, disseminating the same information and advice to the general public is an example of public health malpractice, or negligent public health advice.

The difference is not in the harm that is caused by the two; it is simply in that one comes with liability and the other does not.

Each of these six physicians provides negligent medical advice regarding smoking cessation using electronic cigarettes.

1. Chicago: This advice is negligent because it misrepresents the benefit-risk profile of electronic cigarette use for the individual patient. The physician is telling all smokers that the risks of trying e-cigarettes outweighs the potential benefits. But this is not at all consistent with the science. The science unequivocally demonstrates that there are tremendous medical benefits to patients who are able to quit or cut down substantially using e-cigarettes. And there are essentially no harms because smokers who use e-cigarettes are precisely those who believe they are unable to quit using other methods. This is a complete distortion of the risk-benefit ratio for the individual patient, and it therefore constitutes negligent medical advice.

2. Germany: This advice is negligent because the physician is telling patients that vaping is the same as smoking. This is categorically false. Vaping involves no tobacco whatsoever, and it involves no combustion. E-cigarette aerosol eliminates tens of thousands of the chemicals present in tobacco smoke, including more than 60 known human carcinogens. Switching from smoking to vaping results in dramatic and immediate improvement in respiratory symptoms and lung function. This physician is spreading false information, and it therefore constitutes negligent medical advice.

3. Texas: Like the physician from Germany, this physician is telling patients that e-cigarette health risks are analogous to those for real cigarettes. This is false information, and the medical advice is therefore negligent.

4. Colorado: This physician is telling patients that e-cigarettes are likely no safer than tobacco cigarettes. This is categorically false. Vaping involves no tobacco whatsoever, and it involves no combustion. E-cigarette aerosol eliminates tens of thousands of the chemicals present in tobacco smoke, including more than 60 known human carcinogens. Switching from smoking to vaping results in dramatic and immediate improvement in respiratory symptoms and lung function. This physician is spreading false information, and it therefore constitutes negligent medical advice.

5. Baltimore: This physician is telling patients that vaping harms their lungs. However, there is no clinically meaningful evidence to back this up. While e-cigarette aerosol is a mild respiratory irritant, it has not been shown to affect lung function as measured by spirometry. And it certainly is going to do a lot less harm than continuing to smoke. This stops just short of being negligent medical advice.

6. Minnesota: This physician is telling patients that using e-cigarettes is not a way to quit smoking. Well, it certainly has been a way to quit smoking for hundreds of thousands of Americans who quit smoking by switching to vaping. It is irresponsible for this physician to essentially lie to her patients about the fact that e-cigarettes have helped so many tens of thousands of people to quit smoking. It may not be the way that she wants them to quit, but it is a legitimate way to quit. For putting her own concerns over the best interests of the patient, this is negligent medical advice.

The Rest of the Story

It is difficult to understand what the American Lung Association's objective is here. The effect of this communication is certainly going to be to discourage quit attempts among thousands of smokers who might otherwise have been able to achieve smoking cessation using e-cigarettes. And it might also dissuade thousands of ex-smokers from continuing to vape and instead, cause them to return to smoking. Either way, I don't see how this is in any way helping to improve lung health in this country.

It is, however, public health malpractice, which I define as advice which when given to an individual patient would constitute medical malpractice, but which is instead being disseminated to the general public.

For example, if I tell my patient that vaping is just as hazardous as smoking and therefore I advise my patient not to quit using e-cigarettes, I would consider that negligent medical advice because it is false information and it had the effect of causing the patient to assume an increased risk that he otherwise might not have assumed. Thus, disseminating the same information and advice to the general public is an example of public health malpractice, or negligent public health advice.

The difference is not in the harm that is caused by the two; it is simply in that one comes with liability and the other does not.

Monday, May 16, 2016

American Lung Association and CVS Health Campaign Downplays the Importance of Smoking in Preventing Lung Cancer

Ad Looks Like Big Tobacco Ad from the 20th Century

The American Lung Association (ALA), with primary financial support from CVS Health (CVS), has initiated a campaign called "Lung Force." The campaign features a video ad with the theme of "Anyone Can Get Lung Cancer." Although the ad cites the fact that lung cancer incidence among women has increased over the past decades and mentions radon and air pollution as causes, nowhere in the ad is smoking even mentioned.

I went to the Lung Force fact sheet on lung cancer and found that the #1 most important fact is as follows:

"1. Anyone can get lung cancer."

If you click on the link to get more information, it brings you to the video ad with the theme of "Anyone Can Get Lung Cancer" which doesn't mention smoking.

In a detailed sheet which summarizes the campaign, there is not a single mention of the importance of smoking as a cause of the increasing incidence of lung cancer among women, even though the sheet emphasizes how important it is to get out all the facts and educate women about the "basics" and even though the sheet mentions air pollution, radon, family history, and secondhand smoke as risk factors.

And in a detailed summary of the Lung Force campaign, it again fails to mention smoking. Instead, it de-emphasizes smoking by hiding the fact that smoking is overwhelming the chief cause of lung cancer among women. In fact, it appears that the main objective of the campaign is to downplay the role of smoking in causing lung cancer among women:

"We aim to change people’s minds about what it means to have lung cancer—so that everyone understands that anyone can get lung cancer."

In a long video about lung cancer featuring numerous lung cancer survivors, smoking is not mentioned a single time, other than in an attempt to suggest that smoking is not as important a risk factor for lung cancer as previously thought.

In fact, the campaign actively suppresses the sharing of the fact that smoking is overwhelmingly the leading cause of lung cancer. For example, in presenting Kellie Pickler's involvement in the campaign, sparked by the death of her grandmother from lung cancer, it fails to mention the important fact that her grandmother was a long-term smoker.

The Rest of the Story

I'm not sure that I can overstate my level of condemnation of this campaign. It is disturbing, and it is damaging. It undermines decades of education about the severe health hazards of smoking and about the role of smoking as the overwhelming most predominant cause of lung cancer. About 90% of the suffering that the campaign highlights could be prevented if we made smoking history. But instead, the campaign talks about air pollution, which only causes about 1% (at the most) of lung cancer.

The campaign's theme, and the video ad, look like a Big Tobacco campaign from the 20th century, downplaying the role of smoking in lung cancer by emphasizing that "anyone" can get lung cancer. I'm not sure the tobacco industry itself could have done a better job of downplaying the role of its products in the devastating lung cancer epidemic.

Moreover, not only does the campaign fail to mention smoking as a leading cause of lung cancer and not only does it downplay the role of smoking, but it actively tries to confuse women about the role of smoking. By emphasizing that most lung cancer is diagnosed in nonsmokers and omitting the important fact that most of these women are former smokers, it appears to be intentionally trying to get women to think that smoking is not the predominant cause of lung cancer. Furthermore, it does not once mention the role that the tobacco industry played in the epidemic of lung cancer among women.

The tobacco industry should really send a thank-you note to the Lung Force campaign for running a public awareness campaign that downplays the role of smoking in a way that even Big Tobacco would not do, and is not doing, in the 21st century.

The American Lung Association (ALA), with primary financial support from CVS Health (CVS), has initiated a campaign called "Lung Force." The campaign features a video ad with the theme of "Anyone Can Get Lung Cancer." Although the ad cites the fact that lung cancer incidence among women has increased over the past decades and mentions radon and air pollution as causes, nowhere in the ad is smoking even mentioned.

I went to the Lung Force fact sheet on lung cancer and found that the #1 most important fact is as follows:

"1. Anyone can get lung cancer."

If you click on the link to get more information, it brings you to the video ad with the theme of "Anyone Can Get Lung Cancer" which doesn't mention smoking.

In a detailed sheet which summarizes the campaign, there is not a single mention of the importance of smoking as a cause of the increasing incidence of lung cancer among women, even though the sheet emphasizes how important it is to get out all the facts and educate women about the "basics" and even though the sheet mentions air pollution, radon, family history, and secondhand smoke as risk factors.

And in a detailed summary of the Lung Force campaign, it again fails to mention smoking. Instead, it de-emphasizes smoking by hiding the fact that smoking is overwhelming the chief cause of lung cancer among women. In fact, it appears that the main objective of the campaign is to downplay the role of smoking in causing lung cancer among women:

"We aim to change people’s minds about what it means to have lung cancer—so that everyone understands that anyone can get lung cancer."

In a long video about lung cancer featuring numerous lung cancer survivors, smoking is not mentioned a single time, other than in an attempt to suggest that smoking is not as important a risk factor for lung cancer as previously thought.

In fact, the campaign actively suppresses the sharing of the fact that smoking is overwhelmingly the leading cause of lung cancer. For example, in presenting Kellie Pickler's involvement in the campaign, sparked by the death of her grandmother from lung cancer, it fails to mention the important fact that her grandmother was a long-term smoker.

The Rest of the Story

I'm not sure that I can overstate my level of condemnation of this campaign. It is disturbing, and it is damaging. It undermines decades of education about the severe health hazards of smoking and about the role of smoking as the overwhelming most predominant cause of lung cancer. About 90% of the suffering that the campaign highlights could be prevented if we made smoking history. But instead, the campaign talks about air pollution, which only causes about 1% (at the most) of lung cancer.

The campaign's theme, and the video ad, look like a Big Tobacco campaign from the 20th century, downplaying the role of smoking in lung cancer by emphasizing that "anyone" can get lung cancer. I'm not sure the tobacco industry itself could have done a better job of downplaying the role of its products in the devastating lung cancer epidemic.

Moreover, not only does the campaign fail to mention smoking as a leading cause of lung cancer and not only does it downplay the role of smoking, but it actively tries to confuse women about the role of smoking. By emphasizing that most lung cancer is diagnosed in nonsmokers and omitting the important fact that most of these women are former smokers, it appears to be intentionally trying to get women to think that smoking is not the predominant cause of lung cancer. Furthermore, it does not once mention the role that the tobacco industry played in the epidemic of lung cancer among women.

The tobacco industry should really send a thank-you note to the Lung Force campaign for running a public awareness campaign that downplays the role of smoking in a way that even Big Tobacco would not do, and is not doing, in the 21st century.

Sunday, May 15, 2016

FDA is Defending Deeming Regulations from Well-Placed Criticism By ... ... Lying

Last week on The Source, a Texas Public Radio news show, a spokesperson for the FDA's Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) was confronted with a very solid and well-placed criticism of the agency's e-cigarette deeming regulations. The host asked her how she could defend these regulations in the face of uniform statements by vaping companies that "this is so onerous that this is going to drive them out of the business."

In response, the CTP spokesperson defended the regulations by stating: "It's important to remember that we're talking about products that kill people."

The Rest of the Story

Let's get the facts straight. Yes, it is true that we're talking about products that kill people. But those products are not called e-cigarettes; they're called real tobacco cigarettes.

That the FDA is forced to resort to lying in order to defend its regulations suggests that it realizes it doesn't have a leg to stand on. If there were a legitimate public health reason for putting an onerous, expensive burden on vaping businesses that is going to drive most of them out of business, I'm sure that the FDA would immediately be able to tell us what it is. Destroying thousands of small businesses is not something that we in public health take lightly.

But the rest of the story is that the FDA cannot tell us what the reason is. The only thing they can resort to in defending their onerous regulations is lying. The regulations are needed because we're talking about products that kill people.

Well, let's get one thing straight. The products that are killing people are real cigarettes. And the FDA has chosen to give these cigarettes a completely free ride by putting every possible economic burden in front of much safer smoke-free, tobacco-free cigarettes so that they have little hope of being able to compete with the killer products.

In response, the CTP spokesperson defended the regulations by stating: "It's important to remember that we're talking about products that kill people."

The Rest of the Story

Let's get the facts straight. Yes, it is true that we're talking about products that kill people. But those products are not called e-cigarettes; they're called real tobacco cigarettes.

That the FDA is forced to resort to lying in order to defend its regulations suggests that it realizes it doesn't have a leg to stand on. If there were a legitimate public health reason for putting an onerous, expensive burden on vaping businesses that is going to drive most of them out of business, I'm sure that the FDA would immediately be able to tell us what it is. Destroying thousands of small businesses is not something that we in public health take lightly.

But the rest of the story is that the FDA cannot tell us what the reason is. The only thing they can resort to in defending their onerous regulations is lying. The regulations are needed because we're talking about products that kill people.

Well, let's get one thing straight. The products that are killing people are real cigarettes. And the FDA has chosen to give these cigarettes a completely free ride by putting every possible economic burden in front of much safer smoke-free, tobacco-free cigarettes so that they have little hope of being able to compete with the killer products.

Wednesday, May 11, 2016

First Lawsuit Filed Challenging FDA Deeming Regulations

Yesterday, the first lawsuit was filed which challenges the

legality of the FDA’s electronic cigarette deeming regulations. The suit was

filed in the D.C. District Court by Nicopure Labs, a maker of vaping devices

and e-liquids. The complaint alleges that the FDA deeming regulations are in

violation of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and the First Amendment.

2. The FDA regulations are arbitrary and capricious and impose a huge burden on businesses but without any rational connection to the protection of the public’s health.

3. The FDA’s cost-benefit analysis grossly underestimates the costs while exaggerating, and failing to even quantify the benefits of the regulations.

4. The regulations violate the free speech rights of the company under the First Amendment by prohibiting it from making truthful and non-misleading statements about its products, and without any legitimate government interest.

There are three claims under the APA:

1. The FDA has interpreted the term “tobacco products” way too broadly and in a way which is inconsistent with the Tobacco Act.

1. The FDA has interpreted the term “tobacco products” way too broadly and in a way which is inconsistent with the Tobacco Act.

Nicopure points out that the FDA

has construed the term “tobacco product” so broadly that it includes not only

e-liquids which actually do contain nicotine, but also batteries, wicks,

electronic displays, and glass vials, which do not contain nicotine and are not

derived from tobacco or any constituent of tobacco.

Comment:

This seems like a good point. If I am a manufacturer of batteries for electric

toothbrushes and people start using my batteries in their vaping devices, and I

then put a note on my web site stating that these batteries may be used in

vaping devices, I am now a tobacco product manufacturer under the regulations

and must comply with all provisions. This means I must label my product as a

tobacco product (falsely stating that it contains tobacco) and furthermore,

that I cannot make any changes to my batteries after August 8, 2016, even if

those changes are critical safety improvements, unless I receive pre-market

authorization approval from the agency. If I am a manufacturer of glass vials

and I am reasonably aware that many consumers are using these vials to store

e-liquids, I could possibly be deemed to be a tobacco product manufacturer. If

I advertise that these glass vials would make good containers for e-liquids,

then I am most definitely considered a tobacco product manufacturer.

2. The FDA regulations are arbitrary and capricious and impose a huge burden on businesses but without any rational connection to the protection of the public’s health.

Comment:

The best example of this is the setting of August 8, 2016 as a date beyond

which manufacturers cannot make any changes, including safety improvements, to

their products. That date is arbitrary, as is the treating of products on the

market on August 8th systematically different from products on the

market as of August 7th. Moreover, there is no rational basis for

imposing huge burdens on businesses through the pre-market tobacco application

requirements because these requirements do not directly advance any public

health objective. In fact, the FDA has failed to show that there is any

substantial threat to the public’s health posed by vaping products or that its

regulations will mitigate that threat. There is certainly no rational basis for

preventing companies from making safety improvements to their products after

August 8th.

3. The FDA’s cost-benefit analysis grossly underestimates the costs while exaggerating, and failing to even quantify the benefits of the regulations.

Comment:

This is also a valid point. The deeming rule estimates that there will be 750

PMTAs submitted each year. However, one company alone will submit more than 750

PMTAs. A single company that sells 190 flavors of e-liquid, each in four

nicotine strengths, will have to submit 760 PMTAs. That’s just a single

company. It seems clear that an accurate cost-benefit analysis would have

revealed that the costs of imposing these regulations are astronomical. Moreover,

the FDA did not even quantify the benefits of the regulations. The agency

pointed to no evidence that vaping products are causing public health harm. Nor

did it quantify any of the supposed harms. It is difficult to see how the

hypothetical benefits of regulation, which couldn’t even be quantified, justify

the imposition of literally billions of dollars in capital costs on the vaping

industry, including thousands of small business owners.

4. The regulations violate the free speech rights of the company under the First Amendment by prohibiting it from making truthful and non-misleading statements about its products, and without any legitimate government interest.

Comment:

I believe this is the strongest of the legal arguments. Without question, by

subjecting vaping products to the modified risk provisions in section 911 of

the Tobacco Act, the FDA has prohibited companies from claiming, truthfully,

that their products are safer than real cigarettes, contain no tobacco, produce

no smoke, or produce aerosol that contains levels of certain chemicals that are

much lower than in tobacco smoke. These are all accurate and non-misleading

claims that are in fact essential for consumers to understand, and these are

the primary benefits of the product that companies need to be able to convey.

Moreover, the prohibition of these

truthful claims advances no substantial government interest. In fact, it

doesn’t advance any government

interest. What government interest is there in banning companies from informing

consumers that these products do not contain tobacco? How does that threaten

the public’s health? The truth is that not

informing consumers that these products do not contain tobacco is what will

threaten the public’s health. It will hide from the public critical information

necessary for people to make rational, informed decisions in choosing between

smoking real, tobacco cigarettes and vaping fake, non-tobacco ones.

Because the FDA is prohibiting

truthful claims that are in no way misleading, the test of whether these

restrictions will survive First Amendment scrutiny will certainly be under

strict scrutiny, or under the Central Hudson criteria. The government will have

to show that these restrictions are based on a substantial government interest

and that they will effectively advance that interest.

But I can think of no government

interest in precluding a company which makes a much safer product than

cigarettes from informing its consumers that its product is safer. I see no

government interest in forcing companies to hide from their consumers the basic

fact that their products do not contain tobacco. There is certainly a

justification for forcing ingredient disclosure, but I cannot think of a

legitimate interest that is served by forcing ingredient non-disclosure. I

think it will be quite clear to the court that companies have a right to

voluntarily disclose their ingredients and that the government has no interest

in prohibiting that unless such disclosure would somehow be misleading. In this

case, not disclosing that these

products do not contain tobacco and do not produce smoke is what would be

misleading.

The Rest of the

Story

This is the first of what I imagine will be many lawsuits

challenging the deeming regulations. The First Amendment challenge I think is

extremely strong. There is a high likelihood of success on legal grounds, and

enforcing the modified risk provisions would clearly cause severe and

irreparable harm to the vaping companies. Thus, I think there is a solid chance

that the court will grant injunctive relief and enjoin the FDA from enforcing

this aspect of the regulations while the full case is heard. Because of the

severability of the regulation provisions, only the modified risk provisions

would be subject to injunctive relief under this aspect of the complaint.

It is more difficult to predict what the court will do with

the APA claims. Of those, I believe the flawed cost-benefit analysis is the

strongest claim because it will be easy to show that the FDA greatly

underestimated the costs it is imposing on businesses. Essentially, the FDA

underestimated the cost by at least two if not three orders of magnitude. The

FDA estimated that there would be 750 PMTA’s per year. But the FDA itself

acknowledged that there are 4,600 vape shops that mix their own liquids.

Assuming, conservatively, that each vape shop sells only 10 e-liquid flavors,

this amounts to 46,000 applications. And this is just from small businesses. It

doesn’t include the large e-liquid manufacturers. Given the high likelihood of

success of this argument and the severe and irreparable harm that enforcing it

would produce, I think there is at least a solid chance that the court could

provide injunctive relief on this claim, which would temporarily enjoin the FDA

from enforcing the PMTA requirements.

The other two claims are compelling, but courts generally

give federal agencies a huge amount of discretion when using the “rational

basis” test.

The rest of the story is that Nicopure’s complaint outlines

several compelling arguments which demonstrate that the FDA has exceeded its

authority in its deeming rule in violation of the APA and in a way that cannot

stand scrutiny under the First Amendment. I’m certain that this is only the

first of many more lawsuits to come. This is not unexpected when a federal

agency puts onerous and financially prohibitive burdens on an industry that

result in a de facto elimination of the bulk of that industry.

Tuesday, May 10, 2016

FDA Regulations Present an Imminent Threat to the Safety of the Public: Urgent Changes are Needed

While I have already argued that the FDA deeming regulations pose a long-term threat to the public's health because they will result in the removal of most vaping products from the market (so cigarette sales will continue uncontested), today I explain why these regulations pose a substantial immediate threat to the public's health.

As of August 8, 2016, no new vaping products will be allowed on the market. Because the FDA considers virtually any change in a product to constitute a new product, this means that the deeming regulations will essentially "freeze" the vaping market as it exists on August 8. From that date forward, not only will companies not be able to introduce new products but they will also be unable to make changes in their existing products. Such changes would require a substantial equivalence (SE) determination (which is unlikely because few, if any products are similar to a predicate product on the market in 2007), an SE exemption (which is unlikely because the company cannot show that the product is essentially the same as a predicate product on the market in 2007), or a new product application (which will be prohibitively expensive for most companies). Moreover, these regulations will discourage companies from undertaking any revisions to their products. Several companies have already decided to freeze their inventory and discontinue their innovation research and development.

To be clear, even small changes in products will not be allowed. For example, changes to the battery will not be allowed. If a company wanted to change to a new type of battery in a rechargeable model they produce, this will not be allowed because it would represent the introduction of a new tobacco product into the market for interstate commerce. Similarly, if a company wanted to change their propylene glycol supplier and use a different grade of propylene glycol, this would not be allowed.

The Rest of the Story

The FDA deeming regulations present an imminent threat to public safety. Why? Because after August 8, companies will not be able to make changes to their products to improve product safety.

Suppose company X finds out on August 7 that one its e-cigarettes exploded. The company does an investigation and finds that the batteries they are using do not contain the proper safety features to prevent explosion. The company wants to change batteries in their products to protect the public from an immediate and severe safety hazard. In the absence of the deeming regulations, the company could replace the batteries the next day. But the deeming regulations actually prevent the company from making such a change to its product. You can easily see how these regulations impose an imminent threat to public safety.

Suppose that a company finds a way to prevent potential safety hazards by introducing a new battery overcharge protection system. After August 8, the company cannot do that.

Suppose a company wants to change from a low-grade propylene glycol to a much purer, USP propylene glycol. That would not be allowed because it would represent the introduction of a new tobacco product into the marketplace.

Suppose the company determined that the voltage setting on its battery was too high and resulted in the formation of formaldehyde. Is that company allowed to lower the voltage setting to avoid this problem? Once again, the answer is no because it would represent the unlawful introduction of a new tobacco product into the marketplace.

The regulations will have a chilling effect on product innovation, including safety improvements. This is obviously not in the interests of protecting the public's health. And to the contrary, it actually introduces safety concerns that would not otherwise have been present if companies were permitted to make improvements in their products without pre-authorization.

I can't see how these regulations are going to hold up in court because there needs to be a public health rationale behind them. There is no public health rationale behind the prohibition of product safety improvements.

Remember that in banning the introduction of new products, the FDA is not only preventing the potential introduction of new products that could represent an increased threat to public safety, but it is also preventing the introduction of much safer products.

The rest of the story is that the FDA is essentially freezing any defective products that are on the market as of August 8th, producing a substantial safety hazard.

If defective batteries are on the market as of August 8th, those batteries will continue to explode and cause damage, even if the manufacturers recognize the danger and want to eliminate the hazard.

It should have been clear to the FDA that the requirement for pre-market approval of new cigarettes does not fit the regulation of vaping products. The only reason for the prohibition of new cigarette products in the 2009 Tobacco Act is that there was a history of tobacco industry product changes that resulted in harm to the public's health. For example, companies added ammonia to their products to make them more addictive, introduced light cigarettes to deceive consumers into thinking these products were safer, etc. That is the reason for the pre-market approval for cigarettes.

But it makes no sense to apply that framework to electronic cigarettes because there is no evidence and no reason to believe that companies are manipulating their products in a ways that make them more hazardous to consumers. In fact, it is quite the opposite. For the most part, the innovations that have taken place are improving the safety profile of vaping products. For example, it appears that the diethylene glycol problem has essentially been resolved, we now have many brands on the market which have been shown not to produce detectable levels of any hazardous volatile organic compounds, and the prevalence of unsoldered joints and other manufacturing defects appears to be decreasing.

Since the FDA seems determined to continue to try to force a round peg into a square hole, it is now incumbent upon Congress to intervene and create a new statutory regulatory framework for vaping products. That framework should eliminate any requirements for pre-market approval of vaping products and instead, should require the FDA to simply promulgate a set of uniform safety standards, including batteries that do not explode.

As of August 8, 2016, no new vaping products will be allowed on the market. Because the FDA considers virtually any change in a product to constitute a new product, this means that the deeming regulations will essentially "freeze" the vaping market as it exists on August 8. From that date forward, not only will companies not be able to introduce new products but they will also be unable to make changes in their existing products. Such changes would require a substantial equivalence (SE) determination (which is unlikely because few, if any products are similar to a predicate product on the market in 2007), an SE exemption (which is unlikely because the company cannot show that the product is essentially the same as a predicate product on the market in 2007), or a new product application (which will be prohibitively expensive for most companies). Moreover, these regulations will discourage companies from undertaking any revisions to their products. Several companies have already decided to freeze their inventory and discontinue their innovation research and development.

To be clear, even small changes in products will not be allowed. For example, changes to the battery will not be allowed. If a company wanted to change to a new type of battery in a rechargeable model they produce, this will not be allowed because it would represent the introduction of a new tobacco product into the market for interstate commerce. Similarly, if a company wanted to change their propylene glycol supplier and use a different grade of propylene glycol, this would not be allowed.

The Rest of the Story

The FDA deeming regulations present an imminent threat to public safety. Why? Because after August 8, companies will not be able to make changes to their products to improve product safety.

Suppose company X finds out on August 7 that one its e-cigarettes exploded. The company does an investigation and finds that the batteries they are using do not contain the proper safety features to prevent explosion. The company wants to change batteries in their products to protect the public from an immediate and severe safety hazard. In the absence of the deeming regulations, the company could replace the batteries the next day. But the deeming regulations actually prevent the company from making such a change to its product. You can easily see how these regulations impose an imminent threat to public safety.

Suppose that a company finds a way to prevent potential safety hazards by introducing a new battery overcharge protection system. After August 8, the company cannot do that.

Suppose a company wants to change from a low-grade propylene glycol to a much purer, USP propylene glycol. That would not be allowed because it would represent the introduction of a new tobacco product into the marketplace.

Suppose the company determined that the voltage setting on its battery was too high and resulted in the formation of formaldehyde. Is that company allowed to lower the voltage setting to avoid this problem? Once again, the answer is no because it would represent the unlawful introduction of a new tobacco product into the marketplace.

The regulations will have a chilling effect on product innovation, including safety improvements. This is obviously not in the interests of protecting the public's health. And to the contrary, it actually introduces safety concerns that would not otherwise have been present if companies were permitted to make improvements in their products without pre-authorization.

I can't see how these regulations are going to hold up in court because there needs to be a public health rationale behind them. There is no public health rationale behind the prohibition of product safety improvements.

Remember that in banning the introduction of new products, the FDA is not only preventing the potential introduction of new products that could represent an increased threat to public safety, but it is also preventing the introduction of much safer products.

The rest of the story is that the FDA is essentially freezing any defective products that are on the market as of August 8th, producing a substantial safety hazard.

If defective batteries are on the market as of August 8th, those batteries will continue to explode and cause damage, even if the manufacturers recognize the danger and want to eliminate the hazard.

It should have been clear to the FDA that the requirement for pre-market approval of new cigarettes does not fit the regulation of vaping products. The only reason for the prohibition of new cigarette products in the 2009 Tobacco Act is that there was a history of tobacco industry product changes that resulted in harm to the public's health. For example, companies added ammonia to their products to make them more addictive, introduced light cigarettes to deceive consumers into thinking these products were safer, etc. That is the reason for the pre-market approval for cigarettes.

But it makes no sense to apply that framework to electronic cigarettes because there is no evidence and no reason to believe that companies are manipulating their products in a ways that make them more hazardous to consumers. In fact, it is quite the opposite. For the most part, the innovations that have taken place are improving the safety profile of vaping products. For example, it appears that the diethylene glycol problem has essentially been resolved, we now have many brands on the market which have been shown not to produce detectable levels of any hazardous volatile organic compounds, and the prevalence of unsoldered joints and other manufacturing defects appears to be decreasing.

Since the FDA seems determined to continue to try to force a round peg into a square hole, it is now incumbent upon Congress to intervene and create a new statutory regulatory framework for vaping products. That framework should eliminate any requirements for pre-market approval of vaping products and instead, should require the FDA to simply promulgate a set of uniform safety standards, including batteries that do not explode.

Sunday, May 08, 2016

FDA Draft Guidance Confirms that Deeming Regulations Will Decimate the E-Cigarette Industry

Last Thursday, I provided a review and commentary on the FDA e-cigarette deeming regulations based on my initial reading of the 499-page document released that morning. Now, I have had more time to fully digest the new regulations as well as the draft guidance on pre-market tobacco product applications (PMTAs) that the FDA also released last Thursday. Based on my review, it is even more apparent that these regulations will decimate the e-cigarette industry because the requirements necessary to complete a PMTA are prohibitively expensive for all but the very largest of e-cigarette manufacturers.

The reason for this strengthening in my belief that these regulations make it financially impossible for all but the largest of manufacturers to prepare successful applications is that the draft guidance places extremely burdensome conditions on companies in terms of what they must demonstrate in a PMTA. While the outline below is not exhaustive, these selections from the guidance illustrate the reasons why it will not be possible for most e-cigarette manufacturers to survive.

The Rest of the Story

Below is a sampling of some of the specific provisions of the draft guidance that demonstrate the huge financial burden that the deeming regulations impose on e-cigarette manufacturers. I conclude that a PMTA application will cost a minimum of $1 million - a capital cost that the overwhelming majority of manufacturers will simply not be able to afford. I predict that without Congressional intervention, most e-cigarette manufacturers will take whatever business they can get in the next three years and then find some other line of work. Most will not even bother to submit an application (or if they do, it will come nowhere close to meeting the FDA's guidelines). Another possibility is that e-cigarette companies will trim their inventory down to the bare bones, eliminating most of their flavors and just choosing a small number of products to sell. While this could perhaps result in more companies surviving, it will still decimate the market because it will greatly restrict the choices that consumers have and it will certainly eliminate products that many tens of thousands of current vapers are using.

Moreover, it is not even clear to me that any company - even the largest - will be able to successfully complete a PMTA within two years. As you will see below, the applications will require large, long-term epidemiological studies and clinical trials that I do not think can be completed in 24 months.

1. Every combination of nicotine strength and flavorings will be considered to be a different product.

The draft guidance confirms that even minor differences in e-liquid composition result in a different product, requiring a separate PMTA and a specific showing of public health benefit for that specific product. Thus, if an e-cigarette manufacturer produces four types of starter kits, four types of cartomizers, five types of mods, and 40 e-liquid flavors, each coming in three nicotine strengths, then that manufacturer will have to submit 133 pre-market tobacco applications! This is a conservative estimate, as there are many companies that sell more than 100 flavors of e-liquids. These companies are being required to submit approximately 300 different product applications. The companies have to demonstrate that each one of the 300 different products will be beneficial for the public's health. This alone will be enough to preclude most manufacturers from being able to afford the PMTA process, but it is only the beginning of a long saga.

2. Manufacturers are asked not only to compare the public health implications of their products to cigarettes, but also to other e-cigarette/e-liquids that are on the market.

This is a Herculean undertaking. It is not enough to compare your product to tobacco cigarettes. You also have to compare the public health implications of introducing your product into the marketplace with the risks associated with other vaping products. As the guidance states:

"Because it is expected that consumers of current products that are in the same product category may switch to a newly marketed product, it is important that FDA be able to evaluate whether this switching would result in a lower or higher public health risk. As an example comparison between products within the same category, if your PMTA is for an e-liquid, we recommend a comparison to other e-liquids with similar nicotine content, similar flavors, or other similar ingredients."

This is not something I had anticipated, and it greatly complicates the criteria that must be met to demonstrate that your product is beneficial to the public's health. You not only have to show that it is beneficial compared to real cigarettes, but now you also have to show that it offers public health benefits when weighed against other vaping products that are on the market.

3. Manufacturers are asked to compare the health effects of their products to the health effects of not only cigarettes, but other vaping products as well.

Similar to #2, this adds to the complexity of the task, as you must not only study your own product, but must provide data about other vaping products as well in order to make this comparison.

4. Manufacturers are asked to quantify the levels of aerosol constituents for each product under a range of operating conditions and use patterns.

This means that if you sell an e-cigarette with three voltage settings and you sell 100 flavors, then you will have to quantify the level of aerosol constituents for each flavor at each of the three voltage settings and under conditions of light, medium, and heavy use. Thus, you will have to contract with a laboratory to conduct a gas chromatographic/mass spectrometric analysis of 900 samples. Even at the bargain basement price of $300 for an analysis, we are talking about a capital cost of $270,000 for chemical testing alone.

5. Manufacturers must, for each product, quantify the likelihood that nonsmokers will start using the product, the likelihood that former smokers will relapse back to nicotine use by using the product, the likelihood that nonsmokers who do start using the product will progress to cigarette smoking, the likelihood that former smokers who relapse back to nicotine use will then progress to smoking, the likelihood that consumers will use the product in conjunction with other tobacco products, and the likelihood that smokers who start using the product would otherwise have quit smoking.

Answering these questions will require a huge research undertaking lasting several years and costing millions of dollars. I don't even think that existing NIH research - in its totality - will be able to answer all of the above questions for a single product within two years. Imagine having to answer these questions for each of your products!

These questions simply cannot be answered without conducting clinical trials with hundreds of subjects and costing millions of dollars. I budgeted a bare bones clinical trial to answer just one of these questions at the bargain basement price of $2.8 million. I'm not sure that any company, with the possible exception of tobacco companies, can afford this.

6. Chemical analyses must be conducted on a minimum of three different batches with at least 10 replicates per batch.

So you can scratch everything I wrote in #4 above because now it turns out that the 900 samples that must be analyzed by the typical e-cigarette company outlined above must be analyzed for 10 replicates of three different batches. That brings the total number of analyses to 27,000. Even if a lab offers you an "economy of scale" discount at $100 per analysis, you're still looking at a capital cost of $2.7 million. Moreover, at that volume of sampling, you will basically be occupying the entire resources of the lab for months at a time. There is not even the capacity of chemical testing labs to handle the required volume of sampling so that it can be completed within 24 months.

7. Chemical testing must be done for a minimum of 29 different chemicals, including volatile organic compounds, tobacco-specific nitrosamines, and metals.

OK - so this means that you can throw out the estimate in #6 above because now we can no longer rely on one type of chemical analysis. Now we have to conduct at least two different types of tests because we must quantify metals in addition to volatile organics. So now a typical manufacturer is looking at having to conduct 54,000 analyses in order to keep all its current products on the market. And we're up to $5.4 million in capital costs for the chemical testing alone.